.

Old cannon re-used as bollards

by Martin H. Evans.

Was that bollard once a cannon?

In many towns, cities, villages and ports one comes across things that look like this:

|

|

Are these things old cannon that have been re-used as bollards, or are they commercially made bollards, made to look like an old gun with a cannonball jammed in the muzzle? Well, in the case of these photographs, the bollard outside someone's door in Staithes, North Yorkshire (on the left), was made for civil use to a traditional pattern. The one on the right is a real cannon outside the main gate into the original Chatham Dockyard. It is one of a pair (see the gateway photograph in the gallery below). It had been one of the Royal Navy's biggest smooth-bore muzzle-loading (SBML) guns but when it was no longer fit to be used on a warship it was buried breech-down to protect the brickwork of the gatehouse from damage by carts and other vehicles. The muzzle of this one has been sealed off with a cross-shaped piece of iron.

In various blogs and other internet sites one finds a range of opinions and statements about bollards. At one extreme are assertions that at one time many of London's bollards were French cannon captured from French warships by Nelson's fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. At the other end of the spectrum are people who question whether any bollards had ever been created by burying one end of an old cannon. The purpose of this essay is to show that the truth lies somewhere between these points of view.

There is no doubt that old guns, which were of no further military use, did get used as posts and bollards in the past. Referring to an old iron 9 pdr ("nine pounder" - i.e.: a cannon designed to fire an iron cannon-ball weighing 9 pounds - see glossary below.) that was in the Royal Armouries Blackmore wrote:

"Preserved from a number of guns of the same pattern formerly used as posts on Tower Hill and removed for scrap in 1940 … The practice of using old iron guns as road posts or bollards was started at least as early as the 17th century ('Iron Gunns Broken sett into ye ground')"

(Blackmore 1976, p. 70, catalogue no. 47. See also his notes for catalogue numbers 46, 70 and 150).

There is a print in Blackmore, p. 37, reproduced from "The Graphic" of 1885, which shows a row of old iron guns used as bollards and railings along Tower Wharf. The dust-jacket of Blackmore's book is illustrated by an unidentified old print which shows road posts in front of the Tower of London, and bollards placed to protect corners of the building, that appear to be poorly-drawn cannon buried breech-down with cannon-balls jammed into the muzzles. The print used for the dust-jacket seems to date from about 1800 to 1810.

|

Evidently a lot of road posts and bollards were at one time created by burying one end or other of redundant old iron cannon. In England it seems to have been usual to bury the breech end. Sometimes the muzzle was simply left open, perhaps filling the bore with something such as cheap mortar or even earth. Otherwise the muzzle may have been closed off by jamming an over-sized cannon-ball in, or in some other way. There is an account of a man remembering how a cannon ball was fitted tightly into the muzzle of a bollard in London: "in 1910 as a small boy he saw a bollard being repaired near his home in Clerkenwell. The workmen dug it up and made a fire to heat the cannon mouth. While this was going on one of the crew wound wire round a cannon ball of the correct gauge, making it oversize. When the cannon mouth was red hot, the ball and wire were pushed into the mouth enlarged by heating. As it cooled the mouth firmly gripped the ball." (Personal communication from Mr Andrew Warde).

Old unserviceable cannon did have a scrap value. In the case of bronze guns this was considerable, and when these guns were scrapped they would usually be melted down again for re-casting. Bronze guns salvaged from the wreck of the Royal George in 1841 were said to be valued at £65 a ton, and the copper sheathing at about £100 a ton, after almost 60 years under water (Johnson, 1971). Bronze cannon barrels are sometime incorrectly called "brass" guns. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries these barrels were composed of an alloy of about 86-92% copper, up to 9% tin, with small amounts of zinc and lead (McConnell, 1988). This bronze 'gunmetal' was much stronger than brass (copper alloyed with zinc) and was favoured for land warfare artillery because the barrels were lighter than the thicker-walled cast iron equivalents (Dawson et al, 2007). Cast-iron guns were cheaper to make: in the second half of the 18th century the English Board of Ordnance was usually paying the gun-founders £14 to £20 per ton of gun for new cannon. In the case of old iron cannon, the scrap value would have been low enough for it to have been economical for civil authorities or businesses to buy them, when strong bollards were needed, rather than have purpose-made road posts or bollards cast by a commercial foundry. It can be assumed that this practice would have been commonest in urban areas close to ports, and especially, close to naval dockyards and military depots.

Where did the old iron cannon come from?

Many would have been sold for scrap by the Office of Ordnance, a department of the Board of Ordnance, which was responsible for the development, testing and supply of cannon for military use in England (and later for Britain) from 1597 until it was succeeded by the Ordnance Board in 1855 (Skentelbery, 1965). It is surprising to find that during this period the Royal Navy did not own the "great guns" which armed the Navy's warships. They were supplied by the Board of Ordnance, and installed in the warships from depots of cannon designed for "sea service". Names like Gun Wharf, at Wapping, Portsmouth and Chatham are a reminder of this system. When a warship was paid off, her guns were often sent ashore and returned to the Ordnance depot.

Sales of unwanted military scrap were advertised by notices in the press, and a search of the London Gazette locates many. The sales were usually by sealed tender for large lots, rather than a public auction. Even during the Napoleonic wars the Office of Ordnance was selling large amounts of unwanted cannon and shot. The brief Peace of Amiens perhaps persuaded the authorities to sell off some cannon and shot. For example, this entry in the London Gazette of 2 July 1803 (Issue 15598):

"Office of Ordnance, June 28 1803.

The Principal Officers of His Majesty's Ordnance do hereby give Notice, that they are ready to receive Proposals at their Office, in St. Margaret Street, Westminster, from such Persons as are willing to purchase the following Articles of Old Iron Metal, now lying in the Ordnance Stores at Woolwich Warren:

Old Iron Guns, about 2800 Tons.

Metal arising from unserviceable and unsizeable Round Shot and Shells, about 3000 Tons.

Unserviceable Double-Headed Shot, about 100 Tons.

Old Iron Mortars and Iron Beds, 25 Tons.

No Offer will be accepted for a less Quantity than 100 Tons; and the Purchasers must engage to remove their several Lots within Two Months from the Day of Sale, under Pain of forfeiting the Deposit Money.

The Proposals to be delivered sealed, and marked on the Outside "Proposals for the Purchase of Old Metal."

No Proposal will be received after the 14th July next.

By Order of the Board.

R. H. Crew, Secretary."

There was a similar invitation in the London Gazette of 14 September 1811 (Issue 16522) to tender for about 150 tons of unserviceable shot and cast iron, lying at the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, in minimum lots of 10 tons.

Part of Britain's strategy during the 1793 to 1815 wars with the French Republic and Napoleon's Empire was to capture foreign bases, in order to secure the very profitable trade between Britain and regions such as India and the Caribbean. A lot of foreign ordnance was captured in these conquests. Detailed inventories of captured guns and ammunition were sometimes published in the London Gazette. It is possible that some of these captured guns may have been brought back to Britain. Certainly by 1815, when Napoleon's army had been defeated at Waterloo, large numbers of foreign guns were in British possession. Much field artillery was comprised of bronze pieces. These would have been valuable as scrap, apart from guns that were retained as trophies by Army units. The majority of the guns on warships were iron pieces of less immediate value. Again, some were retained as trophies and can be seen in our Naval museums.

Not all unwanted iron cannon were of Board of Ordnance origin. Most of the iron guns were bought by the Board from iron foundries who made them to an approved design (Dawson et al, 2007). Commercial foundries, including the Carron Company, also cast cannon for private sale to ship owners, because it became common to arm whalers and merchantmen during the war years, to give them protection from privateers (Henry, 2004). These 'civilian' cannon were often smaller than those fitted to RN ships. When peace came, the ship owners probably chose to sell their guns.

As at the end of most wars, there was a large surplus of weaponry after 1815. The foreign cannon were manufactured to fire ammunition (round-shot, cannon-balls) of different dimensions from the standard British equivalents (Dawson et al 2007). That made them even less desirable as working ordnance, so the stocks in British depots were eventually scrapped. It is probable that an invitation to tender for foreign guns, advertised in the London Gazette on 9 August 1836 (Issue 19408) and again on 12 August 1836 (Issue 19409) represented old wartime captures being finally disposed of, 21 years after Waterloo! For some reason the depots in this case were on the island of Jersey.

"SALE OF UNSERVICEABLE IRON ORDNANCE AND SHOT, IN THE ISLAND OF JERSEY.

Office of Ordnance, August 5, 1836

The Principal Officers of His Majesty's Ordnance do hereby give notice, that they are ready to receive tenders for the purchase of the under-mentioned.

Unserviceable Iron Ordnance and Iron Shot at Jersey, viz."

Then follows a list of 71 pieces, all "foreign guns" in 10 lots, totalling about 114 tons, plus several tons of cannon-balls. The pieces ranged from two 24 pdr guns down to two 6 pdrs, the majority being 12 pdrs. The buyers would collect their guns at St. Helier's Pier, and the round shot at Elizabeth Castle, on Jersey. The order was signed by the then Secretary to the Board of Ordnance, R. Byham.

If the cannon-balls were "foreign" they would not have fitted British cannon, being several millimetres oversized. For example, a British 12 pdr fired a cannon-ball 112 mm in diameter. The equivalent French and Spanish guns took balls between 117 and 120 mm diameter (Dawson et al, 2007). Perhaps a few of these were used to close off the muzzles of cannon being reused as bollards?

Similar sales followed from time to time. An announcement in the London Gazette in August 1838, dated "Office of Ordnance August 13 1838", included the statement that "One of the trunnions will be knocked off from the iron guns, previous to delivery to the purchaser." Perhaps by then the Board of Ordnance had become mindful of the possible danger in selling potentially serviceable cannon to foreign or private buyers. As many of the surviving old cannon still in place as bollards in Britain have been buried breech-down, with the trunnions below ground level, often one cannot easily tell whether both trunnions are present or not.

The second half of the nineteenth century saw radical changes in artillery design. Rifled barrels and breech-loading systems for cannon were developed in mid-century. By the 1870s these two innovations had made the muzzle-loading smooth-bore gun obsolete for military purposes in Britain. It seems certain that large numbers of old iron guns would have been sold for scrap soon afterwards. As this was also a period of rapid growth in many British cities, some of these cannon might have been reused as street furniture.

The Trafalgar question

Could some of these guns, re-used as street bollards in London and elsewhere, have been French cannon captured by Nelson's fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805)?

Several personal 'blogs' about London's bollards assert that some were guns from French ships captured by Nelson's fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. This is so unlikely that it seems certain to be a fanciful romanticised 'urban myth'. The evidence against this myth is:

By the end of the battle on October 21st, Nelson's fleet had captured 17 French and Spanish warships (Adkins, p. 219; Clayton & Craig, p. 252). All had severe battle damage and had lost one or more masts - as had most of the English ships-of-the-line. Eight captured ships ('prizes') were completely dismasted (James, Vol. 3, p. 452). The next day a violent storm began that lasted nearly a week. The storm, and a brief counter-attack by enemy ships out of Cadiz, made it necessary for the English ships to stop towing the captured 'prizes' and turn them loose. The French 74-gun Redoutable had been severely damaged early in the battle before surrendering. Around midnight on October 22/23 she sank in the storm (James, Vol. 3, p. 453). Cannon were thrown overboard from several ships to lighten them. Aigle jettisoned many guns including 18 pdrs (Clayton & Craig, p. 333). This was a common practice at that time. A very few captured ships were able to escape back to Cadiz (e.g.: Santa Ana and Algesiras). Most of the other shattered 'prizes' were driven ashore by the storm and beached or wrecked on the coast of Spain during the next few days. In the end, only 4 'prizes' remained in British hands: 3 Spanish warships and the Swiftsure (Adkins, p. 249 & 297; Clayton & Craig, p. 372).

Only three captured 'prizes' were eventually brought back to England: the English-built Swiftsure, and 2 Spanish ships (Bahama and San Ildefonso). Thus, no French-built warship captured at Trafalgar was ever brought back to England, making it virtually impossible for a large number of the French naval guns used in this battle to have become bollards or street furniture in Britain. Even the Spanish 'prizes' might have thrown some guns overboard to help them survive the storm.

The Swiftsure had been an English ship, built at Deptford and launched on the river Thames in 1787. She was an "Elizabeth" Class "Third Rate" 74-gun two-decker ship-of-the-line (Lyon, 1993; Lyon & Winfield, 2004). In 1801 she had been captured by a French squadron in the Mediterranean and was in French hands for just over 4 years until she was recaptured at Trafalgar. She had a re-fit at Toulon, where it seems likely that the French navy would have installed some of their own guns. However, there is some evidence that not all the British cannon were replaced by French ones, and she continued in French service with a mixture of French and British cannon. Having survived the storm (and it is possible that guns, French or otherwise, might have been jettisoned to help her stay afloat) she was repaired at Gibraltar before sailing to Chatham (Winfield, 2007). If she had been fitted with French cannon, they might have been put ashore in Gibraltar. She was later renamed Irresistible and became a prison hulk in the river Medway. There is perhaps a possibility that some French cannon might have remained aboard her until she reached Chatham.

The argument which I have just presented applies specifically to the Trafalgar guns. There is no doubt that many French warships were captured at various times between 1793 and 1815. For example, in the battle off Ushant in June 1794 ("The Glorious First of June") the fleet commanded by Admiral Lord Howe captured 6 French warships and brought them to Plymouth (James, Vol 1, p. 187). The French are said to have lost "upwards of 500 pieces of cannon" (James, Vol 1, p. 195). Some French cannon from these 'prizes' went to the Royal collection in the Tower of London (see below) and at least one gun of similar appearance is still in place as a bollard in Bishopsgate (below). The Royal Navy continued to capture French warships throughout these wars. Two weeks after Admiral Lord Nelson's defeat of the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar, four French ships-of-the-line under Rear-Admiral Dumanoir which had managed to escape from that battle were found by a Royal Naval squadron commanded by Sir Richard Strachan. After a fierce battle, all four French warships surrendered and were taken as 'prizes' to Plymouth (James, Vol 4, pp. 3-12). The repeated successes of the Royal Navy in capturing French warships led to the circulation of the joke that "the most important supplier of ships to the Royal Navy was France". Lists of captured ships can be found in Lyon (1993), Winfield (2008) etc. By 1815 the Ordnance depots will have held hundreds of French naval cannon from captured 'prizes' and it is likely that many of these were later used as bollards. But it is very doubtful whether any were guns that were aboard French men-of-war during the Battle of Trafalgar.

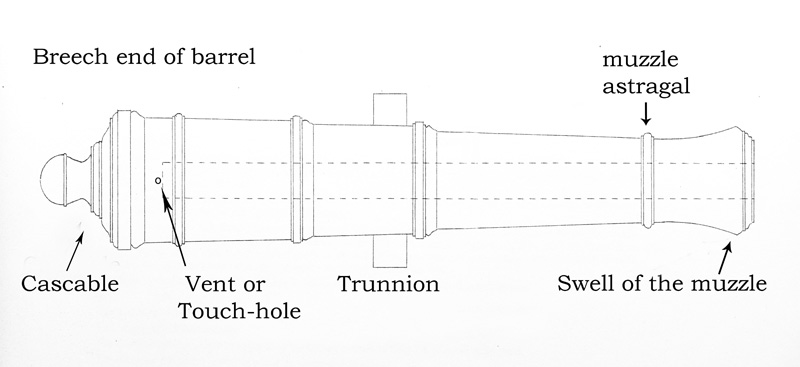

Drawing of a barrel of a smooth-bore muzzle-loading cannon.

|

The drawing above shows an example of a full-length cast iron smooth-bore muzzle-loading cannon barrel typical of one of the guns designed for use by the Royal Navy during the reign of King George II. It is viewed from above. The general design changed little from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries, except that some of the semi-decorative details disappeared or were simplified by the end of this period.

The barrels were manufactured by pouring molten iron into a mould, and letting the casting cool. All the features of the barrel: the trunnions, cascable, astragals, etc were formed in the mould. Some early cannon were cast with a core to create the bore, but during this period the bore (outlined in dotted lines) was made after the casting had cooled, by drilling out on a large machine. The bore ended near the breech and a 'vent' or 'touch-hole' was drilled from the top of the barrel into the blind end of the bore, to allow the gun to be fired by a glowing fuse or flint-spark igniting fine gunpowder in the vent.

The metal at the breech end is thicker than elsewhere and the rear part is called the cascable or cascabel. It normally includes a small knob or 'button' used to secure ropes to. In later guns of this period there was sometimes a ring included in the casting, immediately below the button, for a rope to be passed through.

The trunnions are thick stubby axles that allow the barrel to be swung up or down to get the correct elevation. They were cast so as to be just in front of the centre of gravity, so that the breech would rest on a wedge or adjustable block of wood. Their axis was normally below the axis of the barrel.

The astragals were, in this period, little more than decorative bands that looked like rings around the barrel. They marked the divisions along the barrel from the thickest metal around the breech ('first reinforce') through to the more slender forward part of the barrel ('the chase') that ended where the diameter increased again at the 'swell of the muzzle'.

As well as guns of this type, short-barrel guns such as mortars and carronades were made for special purposes. These would have been too short to be usefully reused as bollards, for which purpose the larger guns, from 12 pdr upwards, would have been suitable.

See also the illustration Cannon diagram which is part of the Wikipedia article Cannon.

Some photographs of old smoothbore cannon re-used as bollards

Some examples that I and some friends have photographed.

I am particularly grateful to Chris Harry, Maggie Jones, Stelios Papadakis, Andrew Warde and Stephen West for letting me use their images.

Old guns re-used as mooring bollards:

Quite a large cannon fixed muzzle-down into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, Pembrokeshire, for use as a mooring bollard. The crab and lobster pots give scale.

Quite a large cannon fixed muzzle-down into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, Pembrokeshire, for use as a mooring bollard. The crab and lobster pots give scale.

Another large cannon fixed muzzle-down into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, as a mooring bollard. This one was buried more deeply.

Another large cannon fixed muzzle-down into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, as a mooring bollard. This one was buried more deeply.

Another old cannon set muzzle-up as a mooring bollard. This one is on the harbourside at Tenby, Pembrokeshire.

Another old cannon set muzzle-up as a mooring bollard. This one is on the harbourside at Tenby, Pembrokeshire.

This old cannon was buried deep into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, and is rusting.

This old cannon was buried deep into the jetty at Tenby Harbour, and is rusting.

Photographed at Chania harbour, Crete, in 1978. This old cannon was being used as a mooring bollard, but has since been removed. The lighthouse at the end of the mole is in the background and a few old cannon survive as bollards along this mole.

Photographed at Chania harbour, Crete, in 1978. This old cannon was being used as a mooring bollard, but has since been removed. The lighthouse at the end of the mole is in the background and a few old cannon survive as bollards along this mole.

This cannon was photographed at Rethymnon, Crete, in 2009. The trunnions are clearly visible and would have been useful to hitch a mooring rope around.

This cannon was photographed at Rethymnon, Crete, in 2009. The trunnions are clearly visible and would have been useful to hitch a mooring rope around.

This mooring bollard at Chania Harbour is barely recognisable as an old cannon, having had its cascabel removed.

This mooring bollard at Chania Harbour is barely recognisable as an old cannon, having had its cascabel removed.

Another mooring bollard at Chania Harbour, almost unrecognisably corroded, but still painted for use.

Another mooring bollard at Chania Harbour, almost unrecognisably corroded, but still painted for use.

A small cannon used for mooring at Lynmouth. The trunnions would have been useful to hitch a mooring rope around.

A small cannon used for mooring at Lynmouth. The trunnions would have been useful to hitch a mooring rope around.

Another small cannon-bollard at Lynmouth. The trunnions are again clear of the ground, and suggest that it had been a rather short gun.

Another small cannon-bollard at Lynmouth. The trunnions are again clear of the ground, and suggest that it had been a rather short gun.

A rusty old gun at Clovelly, one of a number on the quay.

A rusty old gun at Clovelly, one of a number on the quay.

This mooring bollard at Porlock Wier is almost certainly an old gun, buried muzzle-down. Although badly corroded, and without the cascabel, one can just make out the place where one trunnion had been, just above ground level.

This mooring bollard at Porlock Wier is almost certainly an old gun, buried muzzle-down. Although badly corroded, and without the cascabel, one can just make out the place where one trunnion had been, just above ground level.

At Chatham Historic Dockyard these two 32 pdr navy muzzle-loaders were set as mooring bollards at the head of No. 3 dry-dock. In this case the guns were set muzzle-upwards and one can see that one is badly damaged, perhaps in battle. These cannon were the largest ones in regular use on Royal Navy ships from the early eighteenth century until the 1860s.

At Chatham Historic Dockyard these two 32 pdr navy muzzle-loaders were set as mooring bollards at the head of No. 3 dry-dock. In this case the guns were set muzzle-upwards and one can see that one is badly damaged, perhaps in battle. These cannon were the largest ones in regular use on Royal Navy ships from the early eighteenth century until the 1860s.

Another naval gun, this time a 24 pdr, set muzzle-up as a mooring bollard at Pembroke Dock, Hobbs Point.

Another naval gun, this time a 24 pdr, set muzzle-up as a mooring bollard at Pembroke Dock, Hobbs Point.

Large naval guns set as bollards in London's Docklands, near Blackwall Basin. The muzzle design resembles the Blomefield pattern for cast iron sea service guns, which came into use in the 1780s and remained standard RN ordnance for several decades. The bores of these seem to have been sealed with oversized cannonballs when they were reused as bollards.

Large naval guns set as bollards in London's Docklands, near Blackwall Basin. The muzzle design resembles the Blomefield pattern for cast iron sea service guns, which came into use in the 1780s and remained standard RN ordnance for several decades. The bores of these seem to have been sealed with oversized cannonballs when they were reused as bollards.

Another old cannon set as a mooring bollard in the Poplar Dock area of London's Docklands.

Another old cannon set as a mooring bollard in the Poplar Dock area of London's Docklands.

Corner Cannons: old guns placed to protect buildings:

A pair of naval cannon protecting the brickwork at the main gate to Chatham Historic Dockyard.

A pair of naval cannon protecting the brickwork at the main gate to Chatham Historic Dockyard.

An old muzzleloader protecting a corner where two alleys meet. Chatham Historic Dockyard.

An old muzzleloader protecting a corner where two alleys meet. Chatham Historic Dockyard.

Old gun protecting the stonework at a corner at Tower Wharf, London. There are three other old sbml guns set as bollards hear here.

Old gun protecting the stonework at a corner at Tower Wharf, London. There are three other old sbml guns set as bollards hear here.

The old entrance to the navy's Victualling Yard at Grove Street, Deptford. Four large guns protect the stonework and kerbs. The bores seem to have been plugged with old cannon-balls.

The old entrance to the navy's Victualling Yard at Grove Street, Deptford. Four large guns protect the stonework and kerbs. The bores seem to have been plugged with old cannon-balls.

An old cannon protecting the stonework of an archway in Cadiz, Spain. The trunnions are visible at ground level.

An old cannon protecting the stonework of an archway in Cadiz, Spain. The trunnions are visible at ground level.

Two corner bollards at the entrance to an alley in Cadiz. The one on the left is buried muzzle-down; the characteristic cascabel is prominent. The one on the right has been placed muzzle-up, with an old cannonball closing the bore.

Two corner bollards at the entrance to an alley in Cadiz. The one on the left is buried muzzle-down; the characteristic cascabel is prominent. The one on the right has been placed muzzle-up, with an old cannonball closing the bore.

Old gun protecting the corner of a building on Calle Antulo in Cadiz.

Old gun protecting the corner of a building on Calle Antulo in Cadiz.

Muzzle-loading cannon placed to protect stonework at the corner of an alley in Cadiz. The trunnions are clearly visible just above ground level.

Muzzle-loading cannon placed to protect stonework at the corner of an alley in Cadiz. The trunnions are clearly visible just above ground level.

Old gun protecting the corner of a building at an alley in Cadiz.

Old gun protecting the corner of a building at an alley in Cadiz.

This old cannon is set quite deeply into the corner of the building on Arco de la Rosa. A reinforcing band has been fitted around the muzzle swell.

This old cannon is set quite deeply into the corner of the building on Arco de la Rosa. A reinforcing band has been fitted around the muzzle swell.

Another old muzzle-loader set deeply into a building where an alley in Cadiz turns at an angle.

Another old muzzle-loader set deeply into a building where an alley in Cadiz turns at an angle.

Old muzzle-loaders re-used as street bollards, etc.

Old gun used as a bollard outside St Helens in Bishopsgate, London. The shape suggests that it was an eighteenth century French naval cannon.

Old gun used as a bollard outside St Helens in Bishopsgate, London. The shape suggests that it was an eighteenth century French naval cannon.

Pavement bollard in Wapping High Street, London.

Pavement bollard in Wapping High Street, London.

Pavement bollard in Stoney Street, by Borough Market, London.

Pavement bollard in Stoney Street, by Borough Market, London.

Pavement bollard in Bedale Street, Southwark, London. Photograph taken in 2013; this bollard has since been removed.

Pavement bollard in Bedale Street, Southwark, London. Photograph taken in 2013; this bollard has since been removed.

Pavement bollard in Bankside, near the Globe Theatre, London. A relatively long gun of medium calibre. The trunnions have been removed but one can see their stumps part of the way above the ground. This cannon-bollard is mentioned in two of the websites listed below.

Pavement bollard in Bankside, near the Globe Theatre, London. A relatively long gun of medium calibre. The trunnions have been removed but one can see their stumps part of the way above the ground. This cannon-bollard is mentioned in two of the websites listed below.

A group of bollards closing vehicular entry from Swan Lane to Fishmongers' Hall Wharf, at the north end of London Bridge. Two of the bollards are modern commercially made, but three are old cannon. Recent work on the site revealed them to be long guns buried deeply.

A group of bollards closing vehicular entry from Swan Lane to Fishmongers' Hall Wharf, at the north end of London Bridge. Two of the bollards are modern commercially made, but three are old cannon. Recent work on the site revealed them to be long guns buried deeply.

Large bollard with unusual capping near the old brewery in Brick Lane, London.

Large bollard with unusual capping near the old brewery in Brick Lane, London.

Pavement bollard on Cannon Lane, Hampstead, London.

Pavement bollard on Cannon Lane, Hampstead, London.

Pavement bollard in Squires Mount, Hampstead, London. The trunnions are clearly visible, one having been removed in accordance with Board of Ordnance regulations.

Pavement bollard in Squires Mount, Hampstead, London. The trunnions are clearly visible, one having been removed in accordance with Board of Ordnance regulations.

Large gun set as a pavement bollard at corner of Cannon Place, Hampstead, London.

Large gun set as a pavement bollard at corner of Cannon Place, Hampstead, London.

Pavement bollard on the Thames Path in South Woolwich, upstream from the Woolwich Ferry.

Pavement bollard on the Thames Path in South Woolwich, upstream from the Woolwich Ferry.

Two old muzzle-loaders near the old naval dockyard in Woolwich.

Two old muzzle-loaders near the old naval dockyard in Woolwich.

A row of redundant naval muzzle-loaders used to support a lean-to roof in an alley at Chatham Historic Dockyard.

A row of redundant naval muzzle-loaders used to support a lean-to roof in an alley at Chatham Historic Dockyard.

Other photographs of old cannon that have been re-used as bollards, etc.

Historic England maintains a searchable web-site of important historic monuments etc. A search for "cannon bollard" yields many photos, together with their location on a map and other information. Unfortunately, a few of these bollards look to me like commercially made ones 'in the style of an old cannon'. Some expert checking might be appropriate.

Another useful source is the Geograph Britain and Ireland Project that holds millions of photographs submitted by thousands of individuals (I list a few below). It can be searched for bollards, etc.

David Jones has pages about

cannon bollards, aka corner cannons,

still found in Dartmouth, Halifax, Nova Scotia, to protect street corners etc. Also old archive photographs of Nova Scotia that show cannon bollards, especially in the Royal Engineers Garrison.

The web-site Forgotten Galicia has an entry

Reusing Old Cannon in Riga: My Attempt to Solve a Mystery. There are photographs of large iron muzzle-loaders in Riga, Latvia. Placed perhaps to protect walls from vehicles ("guard stones") but maybe also useful as hitching posts for horses. Most of these old guns were planted muzzle-down. Their placement and possible purposes are discussed.

Several photographers have systematically compiled images of bollards, including a few created by reusing old guns, and publish them in blogs or in one of the photographic sites such as Flickr. These people include Maggie Jones who has a large portfolio of Bollards in London and John Kennedy who has a new site: Bollards of London. I have, with their permission, put in links to some of their cannon-bollard photos below as well as using a few of their photos in my general collection above.

Links to photos of bollards made from old cannon:

Outside St Helens Church, Bishopsgate, a large gun has been used as a pavement bollard. It has been photographed by Maggie Jones and by John Kennedy. It is an important item of street furniture, is definitely an old cannon, probably French, buried muzzle-down. The breech end closely resembles Blackmore's Catalogue No. 144:

"Two iron guns, 36 pdrs, French, dated 1787" … "These two guns belong to the series of French naval guns introduced in 1786, the design being attributed to Jacques Charles de Manson, when Inspecteur Général de l'Artillerie des Colonies … The guns were part of the armament of one of the French ships captured in Earl Howe's victory off Ushant on 1 June 1794 … and are first referred to in the 1845 Guide."

It therefore seems possible that it is one of the 'five hundred pieces of cannon' aboard the prizes taken by Admiral Howe, perhaps helping to originate the myth of French guns captured at Trafalgar, as discussed above.

Old bollards, which look like old cannon. Photographed at Woolwich, these bollards are very corroded but look like real guns.

Old cannon now a bollard. On the Thames Path at Woolwich (see below).

An old cannon with cannon ball, now a bollard Blackwall Basin, Isle of Dogs.

There is an old gun near the Thames not far from the modern replica of the Globe Theatre. It had not been buried very deep, so one can see where the trunnions were, although most of them have been removed. It appears on: Knowledge of London and in the Historic UK page "French cannons as street bollards". Unfortunately both of these sites repeat the erroneous myth about Trafalgar.

In Bermondsey, London: Stoney Street, Bermondsey Market. This bollard has the right muzzle profile to be a real cannon.

A bollard in Hampstead, Camden. This one, near Cannon Place, looks as though it might be a real cannon.

Cannon Lane, Hampstead. Another one in Hampstead, with a convincing profile. These appear to be the same bollards that Andrew Warde contributed to the collection shown above.

Cannon set into wall in Steyne Road, Seaford. This is east of Newhaven, Kent. The old gun is severely corroded.

In Southwold. The old cannon had once been set as a "knocking post" at the brewery. It has now been mounted on a modern copy of a naval carriage.

A street-corner bollard in Wapping that is shown on two web-sites belonging to "Ian Visits": An Old Napoleonic Bollard in Wapping? and also Old cannon-style bollard in Wapping. There is a photograph above, sent to me by Chris Harry of a cannon-bollard in Wapping High Street, that looks like the same bollard.

Birmingham Gun Barrel Proof House.

"Faded London" blog shows a number of London bollards, including one that is tentatively offered as a real cannon - I think it more likely to be a commercial street bollard.

St Alfege's Passage, Greenwich. However, this bollard has an octagonal base and is clearly one made as a bollard, in a traditional design.

Mooring bollards made from old cannon:

Abercastle, Pembrokeshire.

Abercastle, Pembrokeshire.

The harbour at Clovelly, Devon. One of the photographs in my main display above shows another one at Clovelly.

Rotherham. This cannon, cast by the great iron-founders Walker & Co, had been reused as a mooring bollard but has now been restored and mounted on a modern copy of a naval gun carriage, outside Rotherham Town Hall.

Bollards on the pier at St Michael's Mount, Cornwall.

Cannon placed as marking points:

Hillingdon. A cannon, at Hillingdon near Heathrow Airport, is said to mark the north-western end of Major-General William Roy's 1784 Ordnance Survey baseline.

Hampton, Richmond and another view of a cannon at Roy Grove, which marks the south-eastern end of Major-General William Roy's OS baseline.

Two photographs: Link one and Link two, of the muzzle of a gun said to mark a 1794 OS baseline in Wiltshire.

Cannon buried for other reasons:

On Steep Holm Island, off Somerset, the Geograph web-site has five photographs taken by Chris Allen, showing old Georgian-period smooth-bore muzzle-loading cannon buried to form pivots for Victorian period rifled coastal-defence artillery. The profile of the muzzles of the pivot-guns is that of the Blomefield design, introduced in the 1780s and still in use into the second half of the nineteenth century (Lavery, 1989; Dawson et al, 2007). Link1, Link2, Link3, Link4 and Link5

A cannon used as a gatepost on a farm near Cranstal, Isle of Man.

An old gun buried near Port Quin, Cornwall, in a tumulus.

A damaged cannon on the Green at Wiveton, Norfolk.

It seems that at one time there were many posts, bollards and other things that were in fact old re-used cannon. Some were taken away for scrap iron in the 1940s "war effort", as referred to by Blackmore (above). In Exeter, for example, Napoleonic-period cannon were removed from a Wellington Memorial during the 1939-1945 war, and melted down as scrap iron. Many other old cannon-bollards have since been removed during development work, and now only a few survive. I suggest that these remaining examples ought to be protected as reminders of our military history.

This essay is "work in progress". I shall be grateful for comments and constructive criticism, whether it is just a note about a "typo" or a whole condemnation of a major error. Please contact me at: evansmartin587 "at" yahoo.com (Edit to get the conventional email format).

Martin H. Evans. © 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019.

First draft: 22nd March 2012. Additions 6 & 21 Sept 2012, 15 April 2014, 5 July 2014, 16 Jan 2015, 25 July 2017, 7 July 2019; version 2 for Wordpress westevan web-page 9 Nov and version 3 11-13 Nov 2019. More images added in 2016, 2017, 2019. Photographs of corner-bollards in Cadiz, Spain, added April 2018.

Abbreviations and glossary

Cascabel or Cascable: the structure at the rear of a muzzle-loading cannon, behind the breech. It normally ended in a knob or 'button' which was useful when handling the gun and as an attachment for a controlling rope in the case of naval guns.

Pdr: pounder. If a gun is classed as a 12 pdr - "a twelve pounder" - it means that the gun was designed to fire a projectile weighing 12 pounds. In the case of smooth-bore guns, the missile would usually be a spherical iron cannon-ball, weighing a nominal 12 Imperial pounds in the case of a British gun. In practice, British 12 pdr cannon fired a 5.4 Kg shot 112 mm in diameter. The bore of the barrel was about 117 mm. The difference of about 5 mm was to allow for manufacturing tolerances and was known as 'windage' (Dawson et al, 2007).

SBML: smooth-bore muzzle-loader. The normal military cannon from the 16th century until the middle of the 19th. 'Rifling', the spiral grooves inside a barrel that made a close-fitting projectile spin during its flight, had been used in costly hunting rifles from the 16th century, but it was not effectively used in heavy ordnance until the mid-nineteenth century. Some very early cannon were made so that the cannon-ball and the charge of gunpowder could be loaded at the breech of the gun. However, the development of better gunpowder for more powerful cannon led to problems in sealing the breech that were not overcome until after 1850. In the intervening period all cannon were cast with a solid breech for strength and the powder and cannon-ball (or other missile) were rammed down from the muzzle. The land army favoured cannon with bronze barrels because they were relatively light in weight. Guns made for naval use were cast in iron because it was cheaper and the heavier weight was less important.

Trunnions: the stubby axles that project from the sides of a gun-barrel, that sit in grooves in the gun-carriage. The barrel can swing up and down on the trunnions, which are usually just in front of the centre of gravity, so that the breech end normally rests on wooden blocks or a wedge (quoin) or a screw under the breech, adjusted to give the necessary elevation.

Bibliography and references

Adkins, Roy (2004) Trafalgar: the biography of a battle. (Little, Brown: London: 2004). Also published as: Nelson's Trafalgar: the battle that changed the world. (Viking/Penguin Group: New York: 2005)

Blackmore, H.L. (1976) The Armouries of the Tower of London. Part I. Ordnance. (HMSO: London: 1976).

Caruana, Adrian B. (1994) The history of English sea ordnance 1523-1875. Vol I: 1523-1715. The age of evolution. (Jean Boudriot: Rotherfield: 1994).

Caruana, Adrian B. (1997) The history of English sea ordnance 1523-1875. Vol II: 1715-1815. The age of the system. (Jean Boudriot: Rotherfield: 1997).

Clayton, Tim & Craig, Phil (2004) Trafalgar: the men, the battle, the storm. (Hodder & Stoughton: London: 2004).

Dawson, Anthony L., Dawson, Paul L. & Summerfield, Stephen (2007) Napoleonic artillery. (Crowood Press: Marlborough: 2007).

ffoulkes, Charles (1937/1969) The Gun-Founders of England. (Cambridge University Press: 1937; Arms and Armour Press: London: 1969).

Henry, Chris (2004) Napoleonic naval armaments 1792-1815. Illustrated by Brian Delf. (Osprey: Oxford: 2004).

Hogg, Ian & Batchelor, John (1978) Naval Gun. (Blandford Press: Poole: 1978).

James, William (1822/1902) The Naval History of Great Britain. (Macmillan and Co: London: 1902 6-volume edition [First published in 1822]).

Johnson, R.F. (1971) The Royal George (Charles Knight: London: 1971).

Lavery, B. (1989) Carronades and Blomefield Guns: developments in Naval Ordnance, 1778-1805. In: Smith, Robert D (Ed) British Naval Armaments. (Royal Armouries: London: 1989).

Lyon, David (1993) The Sailing Navy List. (Conway Maritime Press: London: 1993).

Lyon, David & Winfield, Rif (2004) The Sail & Steam Navy List. (Chatham Publishing: London: 2004).

McConnell, David (1988) British smooth-bore artillery. (Minister of Supply and Services Canada: Ottawa: 1988).

Mehl,Hans (2002) Naval Guns: 500 years of ship and coastal artillery [English translation] (Chatham Publishing: London: 2002)

Ramos Gil, Antonio (2012) Guardacantones de Cádiz: cañones y esquinales. (Universidad de Cádiz: Cádiz: 2012)

Skentelbery, N. (1965) A history of the Ordnance Board. Part I, 71 pp (Ordnance Board Press: 1965).

Skentelbery, N. (1967) A history of the Ordnance Board. Part II, 97 pp (Ordnance Board Press: 1967).

Winfield, Rif (2007) British warships in the age of sail 1714-1792. (Seaforth Publishing: Barnsley: 2007).

Winfield, Rif (2008) British warships in the age of sail 1793-1817. (Seaforth Publishing: Barnsley: 2008).